Where Can We Go From Here?

Breaking down King’s “Racism and the White Backlash” chapter to address conservative ascendancy and potential steps forward

Content note: I haven’t forgotten the series on faith and gender, and actually had started a draft of the next post (sneak peek: it’s about biblical inerrancy). It’s just been slow going due to a busy season of life and healthy doses of video game downtime, so, uh, we’ll see when it comes out.

I’ll start with a bit of a confession: it was hard for me to really pray for the 2024 election. I tried on my way to work on Election Day, but the prayers felt performative rather than heartfelt, with a lot of qualifiers and the overall sentiment of delivering us from ourselves. While I believe God can definitely use whatever type and style of prayer and the general quality doesn’t matter too much, personal experience tells me that these prayers don’t leave too much room for God to work as well.

And I also don’t think the church writ large actually feels the concern. When it comes to Christian witness, the data suggests that most of my fellow Christians actually supported the outcome that came to pass. According to Pew Research, even before the election, 82% of white evangelicals and 54% of white mainline Protestants (61% overall) leaned toward Trump, whereas 61% of white Catholics; they also were more likely to state issues like immigration were very important to their views (and I’m pretty sure they weren’t especially considering Biblical mandates to welcome the stranger while stating those views). Current exit polls state similar numbers. And this isn’t new: in 2016, 81% of white evangelicals (and 58% Protestants overall) supported Trump, the statistic that stood as stark hypocrisy as someone who grew up hearing in church about how Bill Clinton’s moral failings disqualified him to be president. And this is even despite the Republican Party basically repudiating its pro-life platform, which you’d think would upset people who listed that as the reason back in 2016.

I’ve also mostly felt resignation for the Democratic candidates this cycle. Despite mealy-mouthed claims of desiring ceasefire, the Biden administration’s unceasing military support to the Netanyahu regime in Israel has emboldened them to ignore balance of power concerns and instead take aggressively destabilizing swings throughout the region. And after some performative steps in the beginning of her campaign, Harris suggested she’d follow the same failed strategy. More locally, Evan Low, the candidate for the House endorsed by the Progressive Caucus, ran on a pro-police platform and refused to define his views on Gaza (after declaring in the primary that he would not be allowed to live in Palestine due to his sexual orientation). The one clearly risky progressive stance he did take was in opposing Proposition 36, which was clearly not great politically because that’s the one Santa Clara County and the state generally has turned out to support in overwhelming numbers. Rather than be energized, support for Democrats mostly was to escape the specter of a second Trump presidency.

To be clear, I’m disappointed in the outcome, and had Harris succeeded, I would have felt relief and have stayed silent about my qualms (why rain on someone else’s parade and all that). But “save us from ourselves” is a sign that I should probably try to actively conduct change myself rather than expect God to do the work for me. And, that Election Day bike ride, I feel like God convicted me that, regardless of the outcome that day, I should switch from my wishy-washy supplication and to take steps toward making what I want to see happen: a revival of the larger national church, one that finally has the courage to trumpet eternal values of justice, love, and truth, to carry out the democratic vision that all people have guaranteed rights, to insist on the dignity and worth of every individual.

I am weirdly idealistic that this revival is possible, even in the face of the current church that has accepted the devil’s offer of power and influence tied to human leaders. Because of my fluency in church spaces, it’s hard for me to accept the church’s overall embrace of Trump as final. Even the more politically conservative churchgoers I know personally from both home and in Lexington, Kentucky, are more Russell Moore than Lance Wallnau, and they display disdain for the constant scandals and crudeness that mark the MAGA movement. I just don’t believe that Trump is actually that popular a candidate beyond the sizable minority of MAGA-faithful, and perhaps naively think that the vast majority of Americans are still open for a vision truer to core democratic principles.

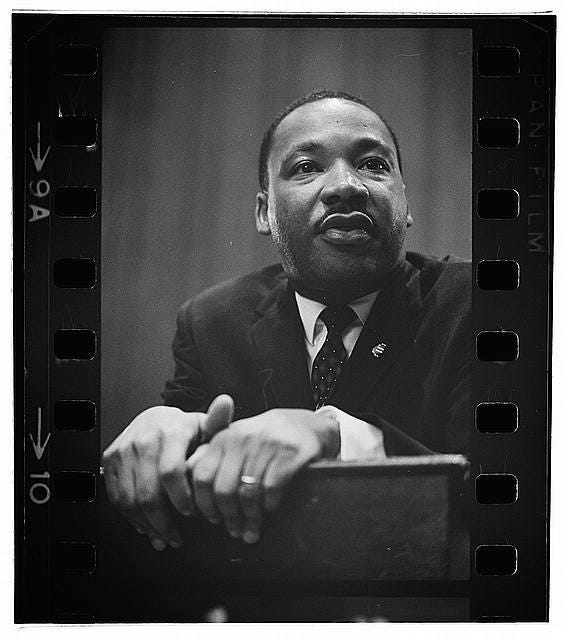

And that’s the headspace that led me to King’s last book, Where Do We Go From Here, specifically his chapter addressing the idea of a “white backlash.” I’ll be honest that while I do see myself as familiar with King’s last years, it’s not my area of focused research and there’s many, many voices on King more qualified than I. That said, basically, the term white backlash gains popularity around the same time of the legislative successes of the 1965 Voting Rights Act and 1964 Civil Rights Act to describe the idea that Americans were getting unsettled by the disruptive protests and demonstrations and stopped lending their support to the progressive campaigns of the period, instead pivoting to support the rise of the modern GOP. Unsurprisingly, it’s also hard to come up with a definition centered around 1964 anymore, as it’s popped up to also explain 2016 and you have/likely will see other political commentary in coming weeks throwing the term around to discuss MAGA-ism and Trump; or to explain why cities across the Bay are recalling progressive district attorneys pursuing police reform.

And as King wrote this book, beyond conservatives, American liberalism has turned on King, viewing his policy proposals to invest real money into addressing inequality nationwide as politically unfeasible and his vocal opposition to the Vietnam War unpatriotic and damaging to American international aims. All that makes a context not too dissimilar from today, as the nation retreats from empty promises of reforming its broken justice system and providing pathways for immigrants to thrive, enabling devastation and genocide to prop up political allies, all while it becomes exceedingly more difficult to achieve the standards of living of past generations.

And to put the TLDR here (this is quite a long post), this chapter insists that the way forward is to keep pushing progressive ideals unapologetically, trusting that there’s still fundamental desire to recognize a dream of full equality, dignity, and intrinsic worth. Another way to sum it up:

Take a broader historical view, one that recognizes that backlashes always occur and that as a nation we’ve also failed to implement our most progressive ideals

Yet there is still a hope/promise/belief in a small-d democratic vision where the dignity and worth of every person is essential, that indeed all people are created equal

Progressive dreams still need more liberal support; liberals, in turn, need to reject their latent prejudices and support broad reforms

Religious leaders have a special responsibility to realize this

So let’s take those points more in depth:

1: Contemporary ambivalence toward the era’s greatest reforms

Back in 1967, political pundits blamed inner-city riots and the Black Power Movement as short-term impetuses for creating the political backlash. Instead, King contended that the newfound resistance to civil rights programs had much more historic roots: “The white backlash is an expression of the same vacillations, the same search for rationalizations, the same lack of commitment that have always characterized white America on the question of race.” While noting that progress had been made since 1619, he detailed that in every era even elite Americans have held ignorant racist views, including prominent leaders such as Thomas Jefferson, George Washington, and Abraham Lincoln. Similarly, grand steps to promote equality, like the Emancipation Proclamation, rarely came with concomitant steps toward implementation (like extending the benefits of the Homestead Act to freed peoples). And, in regard to the then-recent Great Society programs, King noted: “Just as an ambivalent nation freed the slaves a century ago with no plan or program to make their freedom meaningful, the still ambivalent nation in 1954 declared school segregation unconstitutional with no plan or program to make integration real,” nor had it aggressively enforced the 1964 Civil Rights Act or extended meaningful suffrage to all Americans.

And when it comes to my adult lifetime, there have unquestionably been significant positive developments: Affordable Care Act and marriage equality immediately come to mind. Yet I’d be hard pressed to state that either of those areas have had sufficient federal enforcement to produce a truly equal society, let alone the halting steps in regard to reforming police brutality, where Tamir Rice, Treyvon Martin, Sandra Bland, and so many others seem distant memories. So it’s not like political victory would have brought about the Promised Land, as it were: better, definitely, but failing to live up to ideals and then backing down is a pretty common trope in American history.

2: Believe that the nation by and large still can be mobilized by an intrinsic ideal of equality

That said, King then argued: “the racism of today is real, but the democratic spirit that has always faced it is equally real.” I’ll admit that I raised an eyebrow when reading that and I’m still not sure whether I believe that. But King’s prescription is for Americans to realize that to creed and ideal that “all men are created equal; every man is heir to a legacy of dignity and worth; every man has rights that are neither conferred by nor derived from the state, they are God-given” is still possible.

Realizing that, in turn, requires radical reorienting of values: moving money spent in national defense and other pursuits of power to instead finance justice. He observed: “All too many of those who live in affluent America ignore those who exist in poor America; in doing so, the affluent Americans will eventually have to face themselves with the question that Eichmann chose to ignore: How responsible am I for the well-being of my fellows? To ignore evil is to become an accomplice to it.”

And admittedly, to my own jaded ears, this sounds incredibly utopian and out of reach as a way to organize people in 2024, where American political discourse seems very intent on pushing all our problems on some people (migrants, transgender athletes, criminals). At the same time, Scripture backs the idea that wealth is subordinate to faith, that God calls us to show equal honor to the unhoused and the venture capitalist alike. The realist in me is compelled to point out that nations and the church throughout history have failed to live up to that ideal. Yet as a principle to organize around, I think that one is pretty up there as a dream and a vision for a better future.

3: Liberal support is necessary, even as difficult and problematic as it can be

Back in his 1963 Letter from Birmingham Jail, King made the observation that the white moderate can be the most obstinate block to progress, even more than the outright segregationist. Judging from my social media feed, a lot of people read that and assume someone else more conservative than them is the target audience.

But when King revisited the idea a few years later, he replaced moderates with the “white liberal,” people who also acquiesce to injustice even though we feel bad about it. He observed: “even in areas where liberals have great influence,... the situation of the Negro is not much better than in areas where they are not dominant,” oddly citing the church and other institutions (oh, the 1960s). Yet even with the blue state/red state divides today, there are weird quirks that give one pause. For example, when it comes to outlawing involuntary forced labor in prisons, California is actually behind Alabama and Tennessee.

And when it comes to the post-Election Day analysis about why Harris lost, I see a lot of general blame about how the country just is more tolerant of racism, sexism, and general intolerance than people expected going in. That’s a pretty decent summary, but I don’t know how much I can get others to change by pointing that out. But how much of that is because I am willing to tolerate police pushing the unhoused out of my eyesight, to stay silent while someone on Caltrain inveighs on the “illegals,” to throw my hands up about matters of foreign policy rather than to join the campus sit-ins and protests demanding concrete changes that, very likely, would save untold numbers of lives abroad? And this is relevant because when it comes to myself, I do have the capacity to create change on a very concrete level, even as small as it is.

And I also don’t have the luxury to stay out forever. King made this observation: “in spite of this latent prejudice, in spite of the hard reality that many blatant forms of injustice could not exist without the acquiescence of white liberals, the fact remains that a sound resolution of the race problem in America will rest with those white men and women who consider themselves generous and decent human beings.” This line gave me the greatest pause: after all, at this stage, with so many institutions like the Johnson administration and the New York Times abandoning King, I can see King being embittered and spurning the need for their support as unrealistic and impossible.

That said, King spends the rest of this section pleading for the white liberals to change themselves: to be more open to pursuing justice, to back protest, to accept black leaders, and to take more supporting roles than prior in the 1960s.

And so, as it appears still-possible that Trump somehow won even the popular vote, the nudge from King would be to continue to forge the path, again, toward dignity and worth rather than the perhaps politically expedient move to tack to the center, to forget increased immigration as politically unfeasible, to accept the lazy narrative that more police resources alone will make all communities feel safer. I come back to a much earlier King quote, one aimed at the then-uncommitted Kennedy administration:

“Are we seeking our national purpose in the spirit of Thomas Jefferson, who said: ‘All men are created equal … endowed with certain inalienable rights…. Among these are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness?’ Or are we pursuing the national purpose proclaimed by Calvin Coolidge, who said: ‘The business of America is business?’”

And as we think of Kennedy’s achievements, the vast bulk (test ban treaty, proposed civil rights legislation) that are praised come after Kennedy found the will to push through the former path.

4: Religious spaces especially

As someone who spends a lot of time in church spaces, I’m the first to admit that they’re not perfect and certain ones struggle even to hit good (as the rest of this blog seems to attest). And American Christianity especially has seemingly ceded its moral authority for some taste of power, seeking dominion in state affairs even as it sheds adherents and cultural relevance at an alarmingly fast rate. And it’s not exactly like I’m guilt-free in this, even recently: I’ll confess that I’ve compromised as a ministry leader, took the expedient path multiple times in order to preserve harmony, and I’ve already had to apologize to some of my former youth for staying silent on matters of LGBTQ inclusion or excusing a patriarchal system when they would have benefited from my taking a more forthright stand.

But still innate in most religious spaces is the idea of us sharing true equality beyond class, even as that seems a more distant echo in the nation overall. King observed: “‘The image of God’ is universally shared in equal portions by all men. There is no graded scale of essential worth. Every human being has etched in his personality the indelible stamp of the Creator.” That said, much as liberals fail to live out their stated commitments to justice, churches universally fall short of modeling the truth that every person has innate value. I’ve seen firsthand how gender, sexual orientation, age, race, class, culture, national identity, and outward belief system end up creating in-groups that a religious community deems more valuable, and out-groups and Others that it deems less deserving. And this struggle is natural and perhaps even Biblical. After all, while I believe that the Acts 2 model, of believers gathering together, sharing all they have, and building up unity is a worthy goal, we delude ourselves if we set it up as an easily achievable goal possible through human effort. After all, if we just look a bit ahead, say to Acts 5, Acts 6, or Galatians 2, we see instead that even the early church, led by the very people Jesus picked, struggled with accepting all people into its ranks.

And that is my own step of faith: to believe, despite the mounting evidence otherwise, that the church has another path than continued decline and self-inflicted doom; that we have a mission to continue to extol every person’s innate value as an image-bearer of God. As Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel observed from his study of the Hebrew Prophets: “It is an act of evil to accept the state of evil as inevitable or final.” Even if God’s self-appointed mouthpieces and ambassadors are delinquent, the call remains to do justly, to love mercy, to let justice roll down like waters, and righteousness like a mighty stream. And we also do well to remember that God’s promise includes a world where every valley will be raised, every hill and mountain brought low, and that all humanity will witness, on an even plane, the glory of the LORD.